Blonde Roots by Bernardine Evaristo

- natalietarr

- Nov 15, 2024

- 3 min read

Updated: Nov 17, 2024

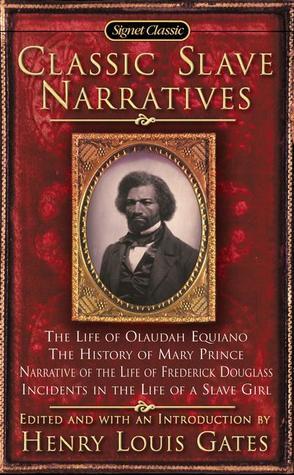

Can you write satirically about the transatlantic slave trade? Evaristo manages the balancing act in this provocative novel. In Blonde Roots (2009), Africans enslave Europeans, capturing, selling, transporting them, reselling them. Would the reversal have changed the ways that people justified their inhuman behavior, their racism, their feelings of cultural superiority? It would not have changed anything, is the storyline of Blonde Roots. We see the world turned upside down, also geographically. Aphrika is situated partly on the northers hemisphere, Europa completely to the south of the equator. Some see in this novel a kind of parody of slave narratives (see for example this MA thesis). For me, it is first of all a book against forgetting. The idea of reversal is not new, we find it in Aux états unis d'Afrique by Abdourahman A. Waberi as well (for this, please click The Africa Bookshelf button). The story of the transatlantic slave trade, the middle passage, and how the whole triangular trade was organized, how it could run so smoothly for so long, and the inconceivable brutality of humans against their fellow humans, is a story that needs to be repeated and remembered. And thus retold. I believe it equally important that we salvage the few narrations we have that are first hand accounts - slave narratives, like the Classic Slave Narratives you see here, which is a compilation of accounts written or told by people who had been enslaved, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. In Blonde Roots,

Doris, an Englishwoman, is enslaved and taken to the New World, New Ambossa, as the fictive place is called. Since the geographical arrangement of continents is turned upside down as well, Evaristo establishes a new order. She rearranges the globe in the rethinks place names. While reading, I had to keep referring back to the map at the beginning of the book, getting confused as to what was where. It also took me a while to get used to the names, at times not really imaginative or funny, such as Londolo, Paddinto, the Cabbage Coast, where Doris was abducted from. But then again the recounting and the names can be quite satirical and funny, for example when Doris is brought to the “West Japanese Islands … because when the “great” explorer and adventurer, Chinua Chikwuemeka, was trying to find a new route to Asia, he mistook those islands for the legendary isles of Japan, and the name stuck” (p. 5). Doris recounts her experiences of tremendous hardship as a field slave in the New World contrasting it with the closeness she finds among her enslaved co-workers. Here, at times, the athmosphere becomes a bit too cozy, I felt, which is part of what has inspired some critics to read Blonde Roots as a parody of slave narratives, see above. The field slaves form improvised families and build friendships across generations, supporting each other as best they can. Like all slaves, Doris is given a new name by her owners and with the loss of her real name she also loses her identity. Her new slave name is a name corresponding to the cultural sensitivities of her owner. She misses her family, dreams of escape and of returning home. Her first escape ends in disaster and her punishment is harsh, marking her physically for the rest of her life. Doris does not give up hope, however, saying that having hope is the only thing she can control in her life. She is convinced she will escape again, which, in the end, she does, this time successfully. Before she gets there, however, she has to endure humiliation, physical punishment, and crass physical labor. The book was at times uncomfortable to read, the descriptions graphic, the horror palpable. And then I thought about that until today, slavery exists across the globe, that humans continue to be cruel to humans, exploiting them for some personal profit, as the numerous organizations populating the www attest to. Bernardine Evaristo's book, written in such a different language than her Booker prize (2019) winning Girl, Woman, Other, is at the same eye-opening, uncomfortable, and spiteful, sometimes giving me a gloating delight in reading how some slavers were weak and ridiculous next to all the cruelty and nastiness they showered on other humans.